With its diverse economy and strong local workforce, Chennai is proving to be a draw for foreign investors. Amar Grover reports

Formerly known as Madras, Chennai is the state capital of Tamil Nadu, one of the largest of India’s southern states. Unless driving through this sprawling city in its dead-of-night calm, the first thing you’re likely to notice is the traffic. Dense, seemingly relentless and apparently governed by the simple maxim that everyone always has right of way, it might prove a stern test of newcomers’ nerves, as well as their vehicles’ horns.

Set by the Bay of Bengal alongside a vast sandy beach, it was here that Britain’s East India Company first gained a toehold on the Coromandel Coast in 1639. Fort St George initially dominated its leased strip of land and its subsequent expansion reflected both sporadic threats (from the French and various regional rulers) and the company’s increasing dominance of South India. The city gradually became the South’s principal naval base and administrative hub.

Today, Tamil Nadu is India’s second-largest state economy. It contributes 8.4 per cent to national GDP and ranks fourth in terms of foreign direct investment. It has more factories and Special Economic Zones than any other state, and ranks third in terms of both gross industrial output and overall exports (which in 2017-18 exceeded US$46 billion). Per-capita income is 31 per cent higher than the national average.

Independent indices also place Tamil Nadu among the country’s most “successful” states. The 2018 Public Affairs Index, published by India’s Public Affairs Centre think-tank, ranked it the second best-governed state. For the second year running, Frost and Sullivan’s 2018 Growth Innovation Leadership Index for Economic Development in India – which evaluates 100 indicators across parameters such as economic prosperity and investment attractiveness – ranked Tamil Nadu second for overall economic development.

Much of this productivity and output is centred on Chennai. With a population of around ten million, it’s the country’s fifth-largest city. The Chennai Metropolitan

Area (CMA) currently covers about 1,200 sq km, comprising the city proper plus extensive suburbs. Unchanged since 1974, there are plans to expand the metropolitan area into surrounding districts (just as New Delhi and Bengaluru have done), possibly adding more than 8,000 sq km.

Many of the country’s largest business entities have anchored their regional or southern headquarters here, and it also hosts 61 Fortune 500 companies. Home to three modern ports (including one of India’s oldest and largest), for decades Chennai has been a vital gateway for the movement of goods in the entire South. Along with Mumbai and Delhi, it’s a significant logistics hub with excellent connectivity by air, road and rail.

Modern Chennai seems more preoccupied with looking ahead than preserving the past. Its George Town quarter, which corresponds to the original British enclave alongside the fort, still boasts several once handsome Raj-era buildings in various states of preservation and decay. Elsewhere, immaculate churches, the huge Ripon Building, imposing Egmore and Chennai Central stations and the university’s extraordinary Senate House remain as splendid as they are functional.

Two sadly insalubrious rivers do little to relieve the city’s throbbing urgency – for that, you’ll need to head to the 6km-long Marina Beach (although at weekends you’ll likely be sharing it with up to 50,000 locals). Neighbourhoods such as Triplicane and Mylapore reveal the city’s more easygoing atmosphere, their bazaars and markets satisfyingly colourful, earthy and a world away from the region’s high-tech corporate sheen.

Wheels in motion

The city’s largest sectors include automobile manufacture, IT, pharmaceuticals and biotechnology, and textiles. While Tamil Nadu is often referred to as India’s “Yarn Bowl” – producing 40 per cent of India’s yarn and accounting for about a third of its textile business – Chennai’s epithet as the “Detroit of Asia” is firmly pegged to its automotive success. Now in the global top ten for automobile manufacture, 45 per cent of India’s vehicle exports originate here, as does just over a third of auto-components. It can produce three cars a minute, one truck every two minutes and a motorbike every six seconds.

Raj Manek, executive director of Messe Frankfurt India, which organises Chennai’s well-established Automotive Engineering Show, says: “The city plays host to a number of global automotive giants who continue to make significant investments in the state.” These include Ford, which opened its first Indian factory here in 1995, Hyundai, BMW and Mitsubishi; France’s PSA Group, which includes Peugeot, Citroen and Vauxhall, is the region’s latest entrant.

Manek notes that these companies have steadily fuelled the city’s huge auto-components industry. “Chennai is still so attractive for major auto-players because of the superior infrastructure facilities, ease of doing business and strong policy support – even tax cuts for certain sectors,” he adds.

Meanwhile, the aerospace and defence sector is rapidly expanding. Between 2013 and 2017, India was the world’s largest arms importing country; by next year its aerospace industry is expected to be the world’s third largest.

The long-planned Aerospace and Defence Corridor, which envisages Chennai as one of several major nodes, aims to attract about $US15 billion in the next 15 years.

Part of this ambitious project includes Aerospace Park, a 200-hectare site in Sriperumbudur (about 40km south-west of the city but still within the CMA) with an advanced computing and design engineering centre.

Overseas interest

Richard Holt, head of global cities research at Oxford Economics, notes that future global GDP growth rates forecast between now and 2035 “suggest that 17 of the world’s 20 fastest-growing cities will be in India. Chennai is likely to be among the strongest performers.” Earlier this year the city hosted the second Tamil Nadu Global Investors Meet. Held in the Chennai Trade Centre – India’s first such venue for international fairs to be built outside of New Delhi – the event welcomed delegates mainly from the UK, France, Japan, South Korea and Australia.

The UK’s 45-member delegation was led by Crispin Simon, trade commissioner for South Asia. According to him, between August 2017 and August 2018 more than two-thirds of UK foreign direct investment into the country went to South India, with Tamil Nadu receiving nearly a third of that. Since 2000, UK companies have created about 55,000 jobs in Chennai alone.

Vijay Krishna, executive committee member of the British Business Group Chennai – a private entity supporting UK trade and business interests here – says that many UK businesses have found opportunities in the automotive, advanced manufacturing and precision engineering, banking, finance and insurance services, and healthcare sectors. He advises: “Any new business entering Chennai will need some preparation and guidance on the various norms, procedures, permits and clearances for specific industries. Its well-established maturity means there are plenty of business-enabling services plus trade and commerce counselling and guidance bureaux that can smooth the process.”

Over and above that, recent legislation such as last year’s Tamil Nadu Business Facilitation Act aims to simplify procedures for new and existing businesses. Part of the act’s regime includes convenient online portals that, given the importance of the IT industry to the state and Chennai, have been long overdue.

India is the world’s largest outsourcing destination and as a whole the sector accounts for about 9 per cent of its GDP. Tamil Nadu ranks third in software exports and generates about 10 per cent of the country’s entire IT exports. The state’s IT and ITES sectors generated US$18.51 billion in revenue and drew US$6.15 billion in investments in 2017-18. “Chennai currently accounts for around 80 per cent of that [output],” says Senthil Kumar, Tamil Nadu senior manager and regional head of NASSCOM (India’s National Association of Software and Services Companies).

In all of that, the city is aided by its strong local workforce. Kumar says: “Chennai’s and other regional educational institutions supply a vast pool of young talent, so there’s huge scope for their involvement in the industry.” The state boasts more than 570 engineering colleges and more than a third of their graduates are from IT and related disciplines. Almost half of its Special Economic Zones are IT/ITES-specific and more than 240 IT parks are slated for development. The government’s Vision 2023 masterplan broadly aims to make the state India’s IT capital by providing the best business climate with world-class skills.

Ahmar Siddiqui, general manager of Taj Connemara – one of South India’s oldest hotels, which reopened last autumn after an extensive refurbishment – agrees that this is an academically oriented city. “Chennai’s education system is renowned across India,” he says “Its alumni find their way into the top echelons of business, government and medicine.”

Pravin Shekar, an entrepreneur based in the city for 20 years, has witnessed all of these changes at ground level. “One thing that’s really helped Chennai is the availability of good-value real estate; it’s unlike Delhi or Bengaluru, although prices are on the up again – usually a good indicator of the local economy’s health.”

Still, Shekar notes that rapid growth has tested the city’s infrastructure. Even as a second airport is still under consideration, the existing one is being upgraded with a large new integrated terminal. Planned to be completed in 2023, the aim is to increase annual passenger capacity to about 30 million.

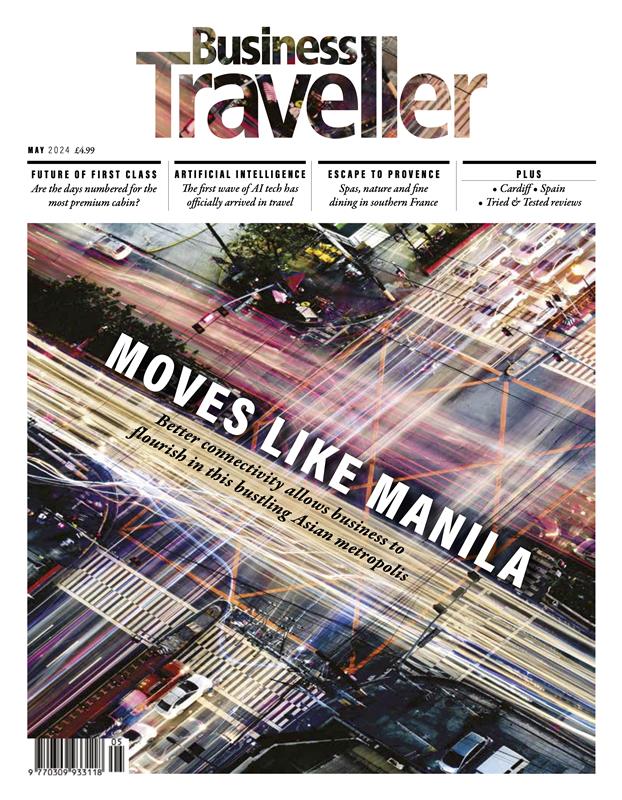

Yet traffic congestion probably remains the biggest issue. The CMA has recently come under pressure particularly from the IT sector (much of it based in the so-called “IT Corridor” along the Old Mahabalipuram Road) to improve side roads, pedestrian bridges and subways, tollbooths and even drainage. Shekar says: “The best thing to happen here is the metro – another [important stretch of] line opened in February which even executives are using; it just saves so much time.” More than 100km further track is planned.

As for Shekar, he still uses a bicycle – so he’s not just brave in terms of entrepreneurship.