According to the European Commission, someone flying from London to New York and back again will generate about the same level of carbon emissions as an average European does heating their home for an entire year.

It’s not unreasonable to question how “flying” and “green” are compatible, yet despite being responsible for a significant amount of greenhouse gases, there are plenty of innovations taking hold – from biofuel to eco-pilot training – that are reducing the harmful impact of planes. And the same goes for airports.

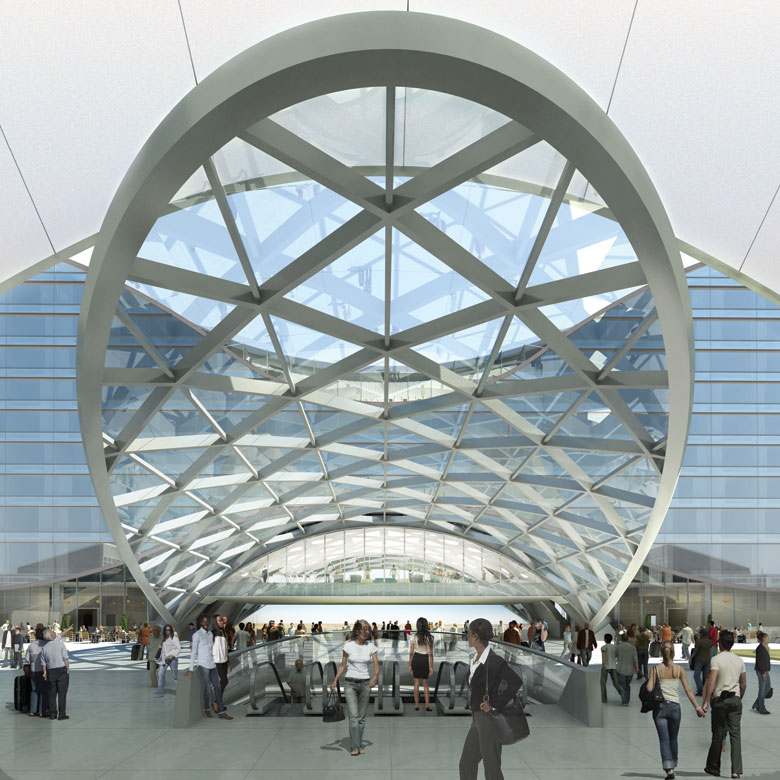

Jim Stanislaski, senior associate at architectural firm Gensler, which has worked on projects including Denver International, New York JFK and the recently unveiled Chennai International, says that in the future, sustainability will be “absolutely” integral to airport design. The reason why? Because “the alternative is not to care and build buildings that pollute even more”.

This seems logical, but what does sustainability actually mean? Stanislaski says: “People, planet, profit – to develop environments that consider the impact on occupants in terms of health and well-being, the [wider] environmental impact, and saving money and resources.”

Of the airports Gensler has designed, he cites San Francisco’s T2 for its sustainable food policies and the Portland International Jetport for its geothermal heating and cooling system, as well as the upcoming Greenville-Spartanburg in South Carolina for its airside garden, and Terminal 2 at Incheon International, which is set for completion in 2017, for its indoor green space.

To recognise those airports that are taking real steps to reduce carbon emissions, Airports Council International (ACI) launched the independently assessed Airport Carbon Accreditation certification in 2009. It’s the only one of its kind and is on its way to becoming the global carbon standard for such facilities. There are four levels – the first being recognition for an airport mapping its carbon emissions, while the fourth (and highest) is for achieving “neutrality” by offsetting emissions.

At the moment, 75 airports in Europe have been recognised (only 14 have neutrality, including Oslo, Milan Malpensa and all ten of Swedavia’s Swedish airports); 12 in Asia-Pacific (there are none at level four and only two at level three – Hong Kong International and Hyderabad); and one in Africa (Enfidha Hammamet airport in Tunisia) at the level one phase.

Robert O’Meara, director of media and communications for ACI Europe, says: “The airport industry is keenly aware that efficiency and sustainability have become vital parts of any 21st-century business. One of the interesting things about this programme is the diversity of the efforts and innovations airports are putting in place to lower their carbon footprints.

“Stockholm Arlanda introduced a rule that incentivised hybrid-technology based taxis, which over time saw all the taxis serving the airport become hybrid/low emissions. The photovoltaic solar park at Athens International is one example of an initiative that is clearly very compatible with the climate there – but it’s not necessarily going to work as an option for every airport in Europe.”

Mouzhan Majidi, chief executive for Foster and Partners – which has worked on Beijing, Hong Kong Chek Lap Kok and Kuwait International, among other airports – agrees that sustainability, in all its permutations, is vitally important: “Airports long ago realised that they are stewards of the environment and very public places – and it’s not just the buildings, it’s the construction process, the vehicles, the way the planes are pulled out to the runway, the handling of waste water, and use of the sun as an alternative energy source.

“But these are all specific to climate and location. Perhaps the most important feature of a sustainable airport is its longevity. This means planning airports that can anticipate and accommodate growth.”

Saving energy to cut emissions is something many airports have been doing for some time. Heathrow is aiming to reduce carbon from energy use by 34 per cent by 2020. After signing the Aviation Industry Commitment to Action on Climate Change (enviro.aero) in May last year, Chek Lap Kok pledged to become the world’s greenest airport, taking steps such as replacing all of its lights with 100,000 LEDs by 2014 (saving 15 million kWh of electricity per year), and creating an all-electric fleet of airside saloon vehicles.

But being sustainable doesn’t end there – here are three emerging environmental trends that are going to shape the airport experience for the passenger.

Biophilic environments

“We need nature in a deep and fundamental fashion, but we have often designed our cities in ways that both degrade the environment and alienate us from nature. The recent trend in green architecture has decreased the environmental impact of the built environment, but it has accomplished little in the way of reconnecting us to the natural world, the missing piece in the puzzle of sustainable development.” So reads the synopsis for a documentary by Stephen R Kellert and Bill Finnegan called Biophilic Design: The Architecture of Life (biophilicdesign.net).

“Biophilia” is the theory that humans have a biological need to connect with nature for the sake of their well-being and health. Kellert adds: “If we were in a room that had no windows, that had just artificial light and processed air, basically you wouldn’t want to be there for very long. And if you were there for very long and somehow you couldn’t escape from that room, you would start to have a kind of a sensory deprivation.”

The narrator of the film’s trailer concludes: “Environmental degradation and alienation from nature are not inevitable consequences of modern life, but rather they are failures in how we have deliberately chosen to design buildings. We designed ourselves into this predicament and we can design ourselves out of it with the help of biophilic design.”

Gensler’s Stanislaski also sees the value in this new approach, and has been working to incorporate it into projects such as Incheon’s new T2, which will feature “a huge indoor garden the size of a soccer field”, adding to the various oases already in the airport, such as an evergreen eco-garden, and flower, cactus and water gardens.

He says: “It’s much more than throwing a few plants and bushes around the terminal – it’s about having views to greenery and incorporating greenery in a significant way throughout.”

He highlights Greenville-Spartanburg International as an example: “It is unique in that it will have an airside garden – it is currently landside but in our new renovation it will be airside so that you’ll be able to sit by a landscaped garden with fountains and wait for your aircraft. You will also be able to sit outside and breathe fresh air.”

Voted the world’s best airport by Business Traveller readers for the past 25 years, Singapore’s Changi has been pioneering this approach for some time. It has a butterfly sanctuary with more than 1,000 species, exotic plants and a six-metre waterfall; a horticulture display; and orchid and sunflower gardens with more than 1,200 blooms between them.

Circadian sensitivity

Jet lag is the bane of frequent travellers’ lives, but innovations in airport lighting may help to ease this in the future, especially when passengers are facing long overnight delays.

At the end of last year, NASA committed to spending US$11.2 million with Boeing on developing “circadian lighting” for its astronauts on the International Space Station to help their bodies keep in sync with their natural sleeping and waking patterns. The coloured LED illumination system will use red, white and blue to help them nod off when they need to and will replace all fluorescent lamps by 2016.

Airports, and even lounges, are notorious for having harsh, flat lighting that remains the same throughout the day and night, and anyone spending prolonged amounts of time in them can find it a draining experience. In the future, it is possible that terminals will take inspiration from NASA, and begin to install lighting that is sensitive to people’s circadian rhythms. A few years ago the US Transportation Security Administration was trialling glowing mauve lights at security to make people feel calmer, and even aircraft such as Boeing’s Dreamliner are fitted with mood lighting as standard.

Stanislaski says: “We are looking at biorhythmic lighting – how illumination affects people’s moods and their circadian rhythms, especially at some of our international terminals where people may be arriving at night. Instead of taking a broad brush and lighting everything evenly, we are looking at how it could change over the course of a day.”

Virtuous concessions

With all the drinking and dining outlets an airport can have, there can be a huge amount of waste. Recycling policies have been around for years, but airports such as San Francisco are now taking this further by selling locally sourced, organic and artisanal produce from nearby farms and vineyards.

Wherever possible, coffee also needs to be fairtrade, seafood must be sustainable and detergents low- or non-phosphate. Vendors in San Francisco’s T2 are also required to use biodegradable containers and cutlery, and separate food waste for composting.

In May 2011, Chicago O’Hare unveiled the largest on-airport apiary in the world, with more than a million bees living in hives. Not only does the project mean thousands of pounds of honey can be collected and sold in the airport (either in jars or as bathing products), but it helps to replenish declining bee populations. This is vital, as about a third of all the food we eat has to have been pollinated by bees, as do around 80 per cent of flowering crops in the US.

Rosemarie S Andolino, commissioner for the Chicago Department of Aviation, which hosts O’Hare’s annual Airports Going Green conference (airportsgoinggreen.org), says: “We also have the first indoor ‘aeroponic garden’ [a method of growing plants without soil] at an airport – we have 26 aeroponic towers that have more than 1,100 plants including fresh vegetables and herbs.

“It doesn’t fully provide all the vegetables and herbs we need at our airport by any means, but it gives us the chance to use fresh, locally sourced products. It’s also a place where people can relax in a quiet, serene location.”

Of course, there are plenty of other initiatives going on behind the scenes at airports worldwide – from harvesting rainwater to generating power from renewable resources such as the sun and biomass waste. But for the passenger, sustainability will hopefully mean a more enjoyable travel experience.